|

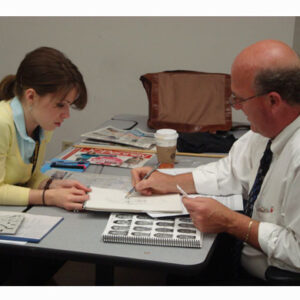

The Cognitive Composite Interview (overview) The police interview or interrogation is typically structured in a “just the facts ma’am” fashion. This method is not conducive to a successful composite drawing interview. Closed-ended, facts only questions limit the witness’s ability to recall information; rather, it can cause the witness to stop thinking and processing his or her perception of the event and just go with the lead of the Detective/Interviewer. A direct or closed interview question may go something like this: Detective: “What kind of car was he driving?” Witness: “Uh, I believe it was a blue SUV.” The same question asked in a more open-ended manner: Interviewer: “Tell me about the vehicle the suspect was driving” Witness: “I’m not real good at knowing the makes of vehicles, but from where I stood, it looked like a blue SUV with four doors. Again, I don’t know the make. Oh, it had kayak racks on the roof. The tires seemed large and the rims were very shiny. It sounded louder than most of the vehicles around at the time. I really couldn’t see the driver because of the dark windows” The difference is remarkable. In the first example, the detective has a blue SUV driven by a male subject. The second open-ended question not only determined that the vehicle was a blue SUV, but that it also has four doors, tinted windows, kayak racks, large tires, and shiny wheels, louder than most, and most of all, the subject was not seen, so there was no way of knowing the gender or race of the driver. The purpose of the Cognitive Interview for Forensic Artists is to obtain the most accurate, detailed, and thorough image of the subject from the witness, to obtain the most accurate likeness possible.  This manner of interviewing the witness, while at times can be uncomfortable for the artist and witness due to the periods of silence. Be patient and allow the witness to recall the information on his or her own. Inevitably the witness will begin to speak, and with it produce additional useful information. Of course, there are times when the witness may gently need to be brought back to the task at hand. This can be done in a variety of manners. You can say something like “you mentioned that the subject’s eyes were brown – tell me more about his eyes.” Just be careful not to lead the witness. Don’t say something like “You said his eyes are brown, so I’m guessing that his hair was dark.” The witness may not feel comfortable refuting your statement or may cause the witness to question his or her recall. You can also bring the witness back to the scene by recalling the events in a reverse chronological manner – “Just before the robbery, what did you notice?” This may put the witness back on track to remembering a detail that he or she previously could not. The single most important skill the artist should remember is: DON’T INTERRUPT THE WITNESS when information is being provided. The witness has information that he or she wants to provide, and you should let it happen. If there is something that you want to know, make a notation on a piece of paper and ask it at a later time. Don’t open the interview with a request for “just the facts:” Allow the witness to answer in a free form manner. Subtle details may be disclosed to the artist by allowing the witness to express what is on his/her mind without pressure by the interviewer. If you ask the witness direct questions, the witness may clam up and begin to furnish answers that he/she believes the interviewer wants to hear. Don’t provide a time frame for completion of the interview: Doing so may place undue pressure on the witness to complete the sketch, resulting in the witness not taking time to find the appropriate photo reference. In other words, doing whatever he/she can do to expedite the interview. Don’t keep looking at your watch, cell phone, or clock: Doing this may make the witness feel unimportant, or that he/she is keeping the interviewer from other duties. Don’t forget to appear calm and interested: Doing so will ease the witness’ stress level, in turn providing accurate unforced information. Don’t work on other cases while your witness is there: Make the witness feel that he/she is the only reason that you are there – that nothing else matters. Don’t stand while the witness is recalling: Standing can be viewed as intimidation. That is the last thing the witness needs to perceive after experiencing a traumatic experience. Don’t talk fast: Speak clearly and at a normal pace. Not only may the witness miss words, but also start thinking about what is said more than recalling the information of the incident in question. Don’t overuse words such as: “like,” “um,” “you know,” “I mean,” etc.: Be cognizant of your verbiage. Using lengthy pregnant pauses, fill in words, etc., will often shift the witnesses’ thought process from thinking about the task at hand to “why is this person constantly saying that word.” Show competence and confidence: Avoid letting the witness see you hesitate while performing your task. Make them feel as if you can draw anything they may describe. Don’t ask questions immediately after a response: Allow the witness time to finish their thoughts process. Answering to fast may cause the interviewer to miss useful information. Don’t interrupt the witness: Allow the witness to speak freely and openly. Let the witness express whatever is on his or her mind. They know what they saw and allowing them to expel that information in their own words is extremely beneficial. The tone or atmosphere of the entire Interview session may hinge on the introductory, pre-interview phase. Some tips to help the interview to get off to a productive start are: The Interview room should be clean, not cluttered o Minimize wall distractions (past composites, bad guys, etc.) o Have comfortable seating The artist should dress casual yet professional o Avoid uniforms (unless your agency requires it) o Avoid suit and tie (while professional, can be viewed as intimidating) o No holy jeans or frayed clothing o No advertisements on your clothing o Don’t expose your weapon to the witness If you use music, make it soothing, and keep it at a background level Greet the witness in a warm and friendly manner – offer a handshake and a smile. Introduce yourself Use appropriate seating arrangement • Avoid sitting directly across from the witness • Avoid sitting right next to the witness • An angled approach seems to work the best Corner of a table separating witness and artist • Allows for witness/artist interaction without over-evaluating the sketch in progress Develop rapport. Get to know the witness – their likes, dislikes, interests, beliefs, etc. Be empathetic, but do not fake that empathy; for, the witness will pick up on it. If you cannot empathize with the witness, tell them as much and use a phrase like “I can only imagine.” This will let the witness know you care without seeming fake. Ask the witness if they need to use the facilities, or would they like water or a soda Let witness know they can take a break at any time during the interview Assure the witness that he or she is the one with the information; it’s their time and their memory that you are going to put on paper. Reassure the witness that the sketch, while wanting to get as close as possible, is but a likeness of the suspect and not meant to be a portrait. The mind does not work like that. Reassure the witness not to worry about describing the suspect wrongly, that the sketch alone will not result in an arrest of the suspect. The sketch is a tool to develop leads, and those leads, or tips may provide investigators the information they need to bring into play the other evidence that has been gathered during the investigation. Explain the sketch process Ask for a general description of the subject in the witness’ own words – anything you can think about him or her; was there anything that stood out about the subject? Ask the witness to describe the face in their own words Explain the catalog (if you are using it). o Explain that although you are looking in one section of the catalog, that they may find the feature that most represents the subject in another section of the catalog, so they should furnish the corresponding code in that section. o Let the witness know they should never feel as if they are interrupting you. |